Friday Reflection: Dorcas, come back: We need you!

Fabrizio Santafede, Dorcas Raised from the Dead, 1611

I call this Early-Church woman disciple, remembered January 27 with two others (Lydia and Phyllis), because I believe we need what I see as one of her great strengths: an admirably nourishing relationship with and within a highly diverse community.

In calling her, I literally echo her own community. According to Acts (Acts 9:36-42), her fellow disciples so revered her that they went to lengths to call her back from death. Rather than simply mourning, honoring, and following her example, they sought to return her among them.

That’s a special community and telling request.

Because of that, I call her today hoping that she can teach us how to BE community in our world and life as she was within her own.

We urgently need that lesson as Americans convulse in fear, rage, and need in so many quarters. Inaugurated on Wednesday after the rioters’ once-unthinkable violations, President Biden and his administration must confront the accumulated nationwide problems that will take many shapes going forward, entangled within a broader world in crisis.

In turn, our work on the ground, as individuals and society, becomes ever more critical. Poet Amanda Gorman called us, at Wednesday’s inauguration, to converge, in all our variousness, on “The Hill We Climb” towards the light from the shade.

Though Dorcas is often portrayed as a saint, she is not listed in the Roman Martyrology. I call on her instead as what we now value as an “everyday” saint. She is closer to us, living peacefully (but for her dramatic return from death) and fruitfully in community, meshing her faith, co-religionists, and a bustling outside world.

My aim, in this Reflection, is to explore what I see in Dorcas that could guide us today, following a review of her story and treatment over time. She left no voice to represent her directly. We build our Dorcas through an early narrator who—aside from describing her return to life—reports only her deeds and the reactions of her contemporaries. My focus will be on her, her witness, though, as we’ll see, she plays an important role in the history and values of the Early Church.

It’s a story that I build gradually, with a few sub-themes, so bear with me.

Dorcas of the Church Writings

We base most of what little we know about Dorcas on the account in Acts of the Apostles, which traces the growth of the Church following Jesus’ ascension. Dorcas’ story is a prominent feature of the early exploits of the Apostle Peter.

As Peter traveled, gaining followers by preaching the Word and performing miracles that convinced witnesses of the power of this new faith, the grapevine quickly transmitted word of his healing the long-sick Aeneas in Lydda. Hearing the news, disciples in nearby Joppa (Jaffa, now part of Tel Aviv) immediately sent messengers requesting Peter’s help for a revered fellow disciple who had sickened unexpectedly and died.

This newest request raised the miracle bar from healing the sick to raising the dead.

The fallen disciple of Joppa was an especially admirable woman, claimed the messengers according to Acts, “full of good works and almsdeeds, which she did,” for a community so diverse that she went by two names, Tabitha and Dorcas (Greek and Aramaic, respectively, for gazelle). Peter agreed, possibly sensing an opportunity to advance the new Church, and hurried to Joppa, given the urgency of burial rites. Upon arriving, he was led to an upper room where Dorcas was laid out. Ostensibly to emphasize her virtues, weeping widows showed “the coats and garments which she had made, when she was with them.” Peter sent all from the room, knelt and prayed (as with Aeneas, invoking Jesus’ intervention), then turned to the body and said, “Tabitha, arise.” When she opened her eyes, he took her hand and, calling the “saints [fellow Christians] and widows, presented her alive.”

What a theatrical as well as pivotal scene! No wonder there are so many images of it like the one shown here. How differently Peter acted from Jesus who swore those present to secrecy (though the stories leaked, luckily for us, and images abounded).

Dorcas’ story concludes with word of this newest witnessed miracle (the first raising of the dead in the New Testament) spreading like wildfire throughout Joppa, gaining even more converts to Christ.

We can assume that, as hoped, Dorcas returned to her exemplary life of devotion and good works until a later well-earned rest in peace.

Much has been made of the story as a key element of Peter’s witness. His miraculous raising of the dead Dorcas, through prayer to Christ, demonstrated his vaunted ongoing link to the risen Son of God and contributed heavily to his building the new Church in its earliest years. His revival of Dorcas thus more broadly provides a crucial milestone in the history of the faith and Church.

Through his intervention with Dorcas, as portrayed by her fellow disciples, Peter also can be seen as publicly certifying her as a model Christian, male or female. His act dramatically foregrounds charity as a Christian virtue. Both Jewish and Christian communities urged generosity of everyone regardless of gender, class, and means, either directly or through gifts to the synagogue or church. For Christians, service to the needy fulfilled the Word. Dorcas epitomized the “doer” of the Word in James 1:22, not just someone who merely heard it.

Selfless and alive with the spirit, such ongoing generosity provided an alternative to Jesus’ daunting mandate for self-perfection: “If thou will be perfect, go sell what thou hast, and give to the poor (Matthew 19:21).” That evangelical guideline led to the voluntary poverty of ascetics from the Desert Fathers to the present.

As the model individual Christian “doer,” Dorcas differs from her contemporary in Jerusalem, Stephen, whose service to the needy, using Church resources (much of it donations), was his official Church job (see my Reflection of December 4).

The Model Christian Woman

Modern bible image of Dorcas sharing her handiwork

For all her value to Peter’s witness and to the Early Church, Dorcas rose to fame as the exemplary Christian woman. Some recent commentators argue that her revival signaled Christ’s special blessing of her witness. Highlighted as a distinguished woman disciple, she was honored over the centuries for her Christian generosity to the needy, especially (but not exclusively) through the admirable needlework that the mourning widows in Acts displayed to Peter. Dorcas made what she shared and shared what she made

With no Scriptural mention of a husband, parents, or children, she became a paradigm of the virtuous, respected independent woman of deep faith dedicated to community through protecting its poor and vulnerable. During those early centuries, the Christian female ideal was a widow of means, the foil of the more familiar poor ones with dependents. In his Morals, rule 74, Basil of Caesarea upholds Dorcas, whatever her actual status, as the model for a widow: “[such a widow] who enjoys sufficiently robust health should spend her life in works of zeal and solicitude . . . .“

Dorcas embodies Christian women’s charity in myriad stained-glass windows especially during and after the 19th century. That is how she appears in St. Stephen’s memorial window for an exceptionally generous woman congregant, the single Anna J. Magee, who died in 1923.

D’Ascenzo Studios, Dorcas, memorial window for Anna J. Magee, after 1923

Today, Dorcas’ example of service to the needy extends beyond faith-based groups named for her, established in the 19th century like that at St. Stephen’s around 1839, to organizations that offer broader resources as well: food and household pantries, social justice, counseling, financial assistance, training, and literacy. Two examples are the Dorcas International Institute of Rhode Island and the Netherlands-based Dorcas.org.

Dorcas’ Capacity to Engage

D’Ascenzo Studio’s portrayal of Dorcas emphasizes what I see as a telling sign of her community engagement: her direct and intimate involvement with the needy as people. She not only hands clothing to the gaunt woman; the two are physically linked. Their gazes connect, the stately standing Dorcas glows compassionately and the kneeling woman conveys reverent gratitude. Dorcas’ left hand rests on the other woman’s shoulder.

This updated Byzantine-style rendering of lofty magnanimity might seem patronizing to us. So I complement it with the account in Acts of the distraught widows at the pivotal death and revival scene. They may have anticipated receiving the garments that they so admired with her death, but they mourned—her, not just the loss of a benefactor.

I see in both examples a Dorcas who engaged personally, effectively.

There’s a new and intriguing added possibility, however: that the weeping widows were Dorcas’ coworkers, even employees, given how well they knew her handiwork. That scenario places Dorcas firmly within a working environment. Instead of being a wealthy (if devout and charitable) doyenne of the dominant class, she is an admired and beloved peer, if not employer. The widows’ description of the clothing made “when she was with them” may refer to their work together.

This proposal comes from Teresa J. Calpino’s recent study (“The Lord Opened Her Heart: Women, Work, and Leadership in Acts of the Apostles;” a 2012 Ph.D. diss. published as a book under its subtitle in 2014) that argues that Dorcas, like Lydia, a cloth merchant, may have been a successful independent artisan-merchant who fabricated her own products, from dyeing to finished goods, for sale. She could have hired others to work with and for her. Her two-story space, instead of being the residence of a wealthy upper-class woman, could be, like those of the period Calpino identified in area archaeological findings, the home and workshop of a thriving tradeswoman.

Such a possibility accords well with Dorcas’ world. Joppa was an ancient seaport that combined major international trade routes with its own strong local business. Prominent among the latter was its textile and garment industry. The city hummed with international and local activity, with multiethnic visitors and residents. Hence the practical value of Dorcas’ two names, both in languages commonly spoken by the area’s multilingual population.

Whether wealthy or simply generous, upper- or working-class, admired in all cases for her strong faith, and capable of genuine bonds with many, Dorcas evidently prospered within Joppa’s multi-level social network. Calpino further argued that the nonspecific description of her charity suggests she may have been generous to all, not just to Christians.

So Dorcas’ community could well have extended beyond the Early Christian circle, adding further layers of cultural variety.

Engaging within a Diverse Community

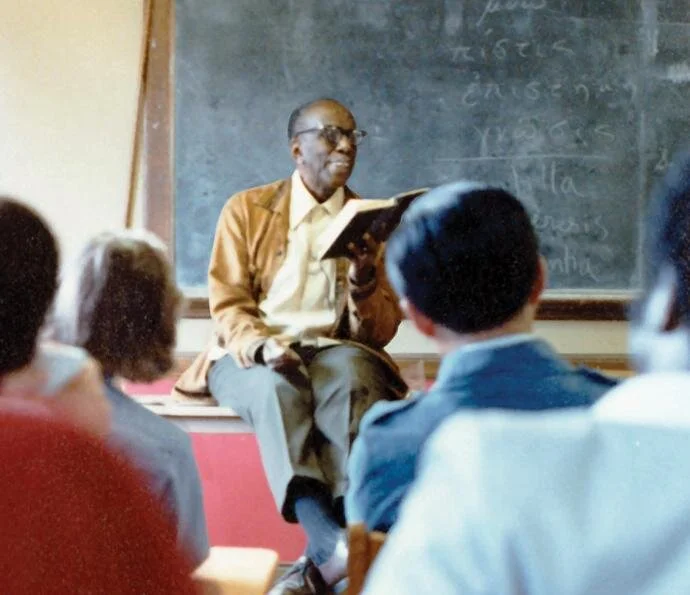

Juan de Juanes, Stephen Before the Sanhedrin, c. 1562

Whatever her personal circumstances, Dorcas provides a telling comparison with Stephen in their apparent approaches to community. Stephen’s Jerusalem, we know from Acts, was fractious as well as heterogenous. Stephen, a forceful preacher as well as deacon, admirably served all, but he died for bearing witness in a strongly-worded, polarizing defense that enraged factions of the Sanhedrin

There’s certainly a place for risky confrontation, for martyrs. Dorcas, however, suggests a quieter but clearly effective alternative for everyday life as well as for crisis. So I return to my initial question: How can she teach us to BE a community that’s as supportive as hers? What did she bring to the mix? Were her high reputation, renowned generosity, and genuine engagement enough? Did she seek peace, de-escalation, rather than confrontation? Did she, possibly a woman in trade, listen, find a mutually satisfying agreement? Did she respect and work with different views and goals? As a devout Christian, did she approach a potentially polarized world with humility and love of one’s neighbor? Did obvious empathy and compassion build trust and cooperation?

Whatever, her community wanted more. They wanted HER back.

Dorcas, show us a way for today. . . .

—Suzanne Glover Lindsay, St. Stephen’s historian and curator