Friday Reflection: Eric Liddell II–Humanity Revealed in Internment

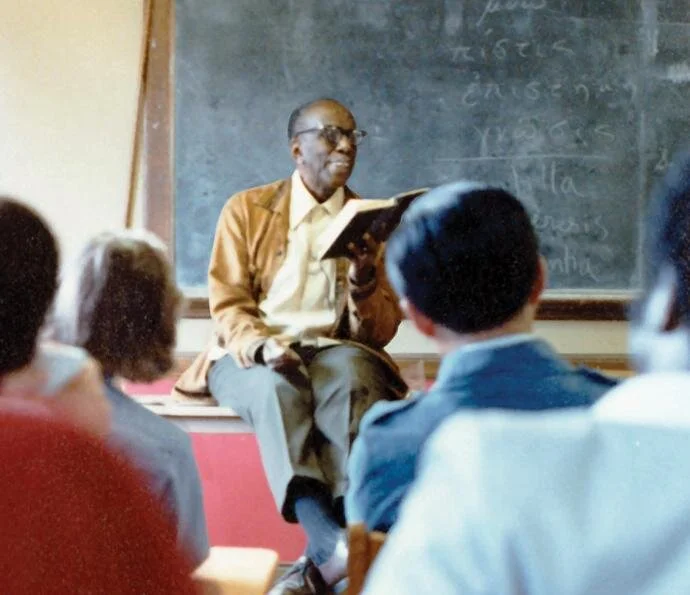

Eric Liddell Joins the Global Hymn Sing 1942

Summary of Part I: Eric Liddell (1902-1945), whom the Church honors on February 22, was a focus of the Oscar-winning 1981 movie Chariots of Fire. He was a celebrated devout Scottish sprinter who defied public and official opinion by refusing to run on Sunday for the 1924 Paris Olympics. After winning a gold medal and world acclaim in a challenging event on another day, he left for his native China as a missionary. Our story begins precisely there: Eric was reportedly widely revered, even deemed a saint, for his missionary work in wartime China. Why, I wondered, and what do he and his experience teach us today? Part I of this Reflection (February 5) considered his early missionary family life in a tumultuous China and his call to Evangelical ministry at Edinburgh University while he gained international fame as a rugby player and sprinter. This devout athlete became the ideal modern British Christian male, the Muscular Christian, thus an ideal Evangelist to modern men. Eric spent 20 years as a missionary in China, first to the Chinese and, in 1943, to his community in a Japanese internment camp for enemy aliens.

Eric Liddell’s camp was NOT among the familiar types of World War II: camps for captured soldiers; the Nazi civilian camps; and those in the United States for captured Axis soldiers and for civilians linked by blood to Axis countries (mostly Italy, Germany, and Japan). Like their predecessors, those left painful scars.

Japanese civilian camps also varied.

Once civilians decided to stay in China, knowing that internment camps loomed, they were given time to prepare in early 1943, then were assembled for transport in March to camps throughout the country. Eric Liddell went, with about 1800 other people, to the largest, Weihsien Camp, near present-day Weifang in Shantung (Shandong) Province. Many lived there for over two years until liberated in August 1945.

Former internees at Weihsien strongly emphasized their relatively good fortune. For all their hardships and fears, they fared far better than those in Japanese camps elsewhere in Asia, especially the Dutch East Indies which held 130,000 Allied civilians, most of them Dutch (iwm.org.uk). Conditions and treatment were notoriously brutal. 14,000 died in those camps. Some commentators link this ferocity to Japan’s collaboration with local nationalists aiming to free their country of its centuries-old foreign colonial power. A revolution enabled by the world war transformed the Dutch West Indies into Indonesia.

Weihsien

Weihsien, built as an American Presbyterian mission, had been a generous compound with landscaped grounds, a boarding school, church, and a modern hospital that were looted and vandalized by occupying troops afterwards. When the complex became a “Civilian Assembly or Internment Center,” the Japanese occupied the missionaries’ homes in a walled-off area; internees received the “working” area standardly measured at 150 x 200 yards.

Aside from watchtowers, barbed and electrified wire on walls, roving guards, morning roll call, and meetings with administrators, the internees rarely saw their captors. There were no reports of the brutality elsewhere: no forced labor or prostitution, rape, torture, and execution.

Why? First, Weihsien was in a nominally Chinese territory; its Japanese staff, even the guards, were consular civilians, not military. I don’t know how many administrators and guards lived there. Interaction varied. The official charged with housing was courteous and responsive; guards ranged from kind to bullies and even buffoons whom internees enjoyed teasing. Outgoing messages through the Red Cross were nonetheless censored and often destroyed, or neglected.

Secondly, these internees were likely potential currency for trade, so their welfare was critical. Americans were soon exchanged for Japanese prisoners, as were Roman Catholic religious arranged by the Vatican. In the two years of the camp’s operation, over 2100 people reportedly lived there, 1600-1800 at one time. They represented many countries, ethnicities, lives, and ages.

Though many internees wrote of the physical hardships, they shaped a life that one among them startlingly called “almost normal” but for the oppressive sense of its precariousness and the unknown.The internee who articulated that view was Langdon Gilkey, a young American university professor who became an eminent liberal ecumenical theologian. He observed in his 1966 memoir of the experience: “our problems were created more by our own behavior than by our Japanese captors” (Gilkey, Shantung Compound, ix). That, he said, is what makes Weihsien’s story so unique and relevant to our own lives.

Block 58, Weihsien today

Human Nature Revealed at Weihsien

The relative independence permitted at Weihsein was a mixed blessing. Internees built and managed the huge community within the restricted and wrecked complex. They governed by council, with committees that reported, through Japanese administrators, to the Commandant. They constructed primitive facilities, refurbished the hospital, and organized essential physical services. Living spaces were so confined that residents were packed in like sardines, usually in bunk beds, with little room for belongings or moving around.

All able-bodied were assigned chores. Teams prepared meals for thousands, in several kitchens, from food provided by the Japanese, which was meager, intermittent, and of poor quality. The Japanese-supplied canteen and black market with the neighboring Chinese provided purchasable treats.

Communal life in tight spaces, however, demanded collaboration and sacrifice. Human nature being what it is, problems soon emerged; among them:

Reaction to overcrowding and lack of privacy: quarrels, fights, obsessive territoriality, risky sexual activity especially among teenagers (no medication);

Effects of food insecurity: resistance to sharing with the needy, hoarding, theft of food and others’ belongings to pay for special items.

How can the council govern this community with no consequences beyond public shaming (which regularly failed)? The rare Japanese interventions were light. How do you establish a moral infrastructure in a fragile limbo with no known outcome? Problems of values, self-definition, and social bias predictably surfaced, given the vast diversity.

Gilkey saw a profound moral breakdown that was as serious as outbreaks of dysentery or loss of bread. Yet strong moral health drove individuals from often-unlikely communities who pitched in, dissolving old social lines. “Respectable” groups shunned a European prostitute working in China until her grit, energy, and people skills won respect and demand for her help especially with challenges. The reeking, malfunctioning toilets, once missionaries mucked them out and stabilized them, were regularly cleaned by an unflappable upper class British colonial matron.

Unity and positive interaction came often from the religious, the “means of grace” to the entire community (Gilkey, 172). Orthodoxies were bent: Trappists, released from seclusion and vows of silence, engaged boisterously. Grace also emanated from Salvation Army missionaries who tended the needy who couldn’t contribute.

For Gilkey, Weihsien revealed a crucial relationship between religion and the world: “seeking justice for material things for one’s neighbor is perhaps the highest of spiritual attainments, since it is the expression in social relations of what it means to love one’s neighbor (p. 229).”

Where did Eric Liddell fit in?

Eric Liddell became Gilkey’s consummate modern religious in his selfless sharing with fellow internees. Gilkey’s respect for Eric is often quoted: “It is rare indeed when a person has the good fortune to meet a saint, but [Eric] came as close to it as anyone I ever met” (Gilkey, 192). Gilkey’s admiration, as a young, very liberal academic, for this Evangelist emphasizes his evolved appreciation of difference and bending orthodoxies. Eric’s official job, as a longtime teacher, was to manage teenagers and children. Ever the Muscular Christian, “Uncle Eric (a Chinese honorific),” organized activities, including sports, to channel energy, lift morale, and build esprit de corps. He ran in races that he deliberately lost to encourage others and organized square dances though he didn’t participate on religious grounds.

And, as the highest form of bending with circumstances, he allowed games on the Lord’s Sabbath.

He was also everywhere: tending the sick in hospital; consoling the troubled; fixing broken gear.

Eric’s own approach to internment was infectious: the springy step, smiling face brimming with humor and love of life. Some claimed he was their daily dose of goodness.

He was also the community’s moral force: “the camp’s conscience without ever being pious, sanctimonious, or judgmental. He forced his religion on no one” (Duncan Hamilton, For the Glory. . . , 8).

There was at least one camp congregation. Eric, an ordained Congregational minister, led meetings and taught religion privately, from the Bible and his own book, Discipleship, a selection of maxims from various sources.

One internee, later also a missionary, portrayed Eric’s “secret“ even in internment thus: “He unreservedly committed his life to Jesus Christ as his Saviour and Lord. That friendship meant everything to him” (David J. Michell, EricLiddell.org).

Dr. Michell did not distinguish between Eric’s work with the Chinese and multinationals of the camp. Perhaps Eric didn’t either, or perhaps he felt called separately to the latter as war evolved. Both formed part of China as communities in crisis needing the reassurance of divine presence.

I can only speculate about Eric’s views or quote others because he was silent about himself in camp, unlike his earlier years when he spoke regularly about his calling. Members of the camp congregation noticed and decided he’d channeled himself totally into selfless service (Hamilton, 9).

We do know that Eric began his day privately with God, in claustrophobic quarters studying the Bible and praying with a roommate, missionary Joe Cotterill, for an hour.

His faith in divine presence and support in crisis, however, carried forcefully in his favorite hymn, which he had sung regularly in camp for its comforting message to others, Katharina von Schlegel’s 1752 lyrics (1855 English translation by the Scottish Jane Borthwick) set to Sibelius’ beautiful 1899 Finlandia:

“Be still, my soul; the Lord is on thy side;

Bear patiently the cross of grief or pain;

Leave to thy God to order and provide,

In every change he faithful will remain.

Be still my soul; thy best, thy heavenly friend

Through thorny ways leads to a joyful end.”

Eric Liddell Joins the Global Hymn Sing, 1942

As his health mysteriously deteriorated, he requested this hymn from the Salvation Army band that serenaded him outside his window. Eric Liddell died at age 43 on February 21, 1945, taken, it turns out, by a brain tumor.

Remember Eric Liddell on February 22, his official Church commemorative date following that of his death. There is much to honor in his life. I hope for such selflessness, sincerity, and uplifting joy in our own world and to learn from his example myself.

There is also much to learn from the “ordinary life” at Weihsien. Its many stressors are eerily familiar today: our selfish urge to jump lines for Covid19 vaccine; the anguish of insecurity in housing and food suffered by so many; the overcrowding and lack of privacy in pandemic, the streets, and shelters. We too have a world in need, in crisis. As Gilkey noted from Russian Christian philosopher Nikolai Berkyaev, “To eat bread is a material act, to break and share it a spiritual one.” There are so many ways to share bread.

—Suzanne Glover Lindsay, St. Stephen’s historian and curator