Friday Reflection: On Benedict of Nursia – To Work and to Pray as a Rule of Life

If anyone would like to get a true picture of this man of God, let him go to the Rule he has written, for the holy man could could not have taught anything but what he had first lived.

—From Saint Gregory, Dialogues II

Listen carefully, my son, to the master’s instructions and attend to them with the ear of your heart. This is advice from one who loves you; welcome it and faithfully put it into practice.

—From the Prologue of The Rule of Benedict

Read Benedict of Nursia’s biography here

I. We don’t know very much about Benedict of Nursia, whose life and work are celebrated on Saturday, July 11. There are no scholarly studies about him from his time (c.480 – c.550), though there is a great deal of contemporary writing about him and his “Rule of Benedict.” Virtually all of the reliable biographical information we have comes from the second volume of the Dialogues of Pope Gregory I, written in 593-94. Here is what Gregory tells us. Benedict was born in Nursia in Central Italy into a “family of high station.” In his mid-teens, he was sent to Rome to continue his literary studies. Once there, he experienced a Rome in decay, an empire that was at the end of its life. Manners and morals seemed non-existent, political instability was increasing and, for Benedict, all the signals suggested a massive societal breakdown. Benedict decided he wanted nothing to do with Rome and was afraid of what might happen to him, that he could end up leading a dissolute life, so he fled Rome and looked for a place of moral and emotional safety.

II. Benedict found such a place in the mountainous area of Subiaco, about 40 miles from Rome. Gregory suggests that Benedict spent five years or so in the Subiaco area, three of which he spent in a cave, living mostly in solitude. In this period, Benedict reached a greater spiritual depth and in clearer sense of how he wanted to live in the world. He became involved with some monks of several small monasteries around Subiaco, earning their great respect and admiration, so much so that Benedict was soon seen as someone who could be the abbot of a monastery; indeed, one of the monastic communities asked him to become their abbot. He agreed but after some time and no little animosity, it became clear that Benedict was not the right person to lead the community. Yet, as he became more well known, especially by more fervent followers and other monks, new small monastic communities were formed, and Benedict became the abbot of one of them. Over time, however, Benedict became concerned about the disorganization of these small monastic communities and around 529, taking a small group of monks with him, he went to Monte Cassino, a place 80 miles south of Rome, and established a new and eventually very important monastic community. Benedict remained at Monte Cassino until his death.

III. It was at Monte Cassino that Benedict imagined a new model of Western Monasticism and where in 540, he wrote the Rule as the instrument with which to create this “new model.” Monte Cassino was Benedict’s workshop and his experience as the abbot of this monastic community, helped him shape and formulate his thinking about the need for such a Rule and what its elements ought to be. The Rule included a Prologue and 73 short chapters (a mere 9000 words). Benedict created it as a means for monastic communities to achieve sensible organization, informed governance with a clear mandate, wise and fair discipline, spiritual direction—a community that was grounded in prayer and work.

IV. Over time, it has become clear that Benedict’s Rule was not altogether original. It is now widely understood that Benedict “borrowed” from the sayings of the Desert Fathers, from The Rule of Saint Basil, from the Conferences of John Cassian, and most notably from the Regula Magistri (Rule of the Master), written by “The Master” in Italy in the period between 500-525. This is important background for it confirms that Benedict was a zealous student of monasticism and of the “monastic impulse” that helped make the Rule a remarkable spiritual and organizational document which articulated a meaningful way of life for those called to prayer, to study, to work and to life in a community. It is clear, comprehensive, empathic, practical and very much a teaching document, especially around the demands of leadership and the experience of community. It is also surprisingly worldly as, while the Rule focuses on spiritual formation and organizational structure, it is also intended to provide a consistent world view for the monks. It acts as a “guide” to seeing and hearing and a “how-to” manual for the maintenance of a healthy and vibrant community.

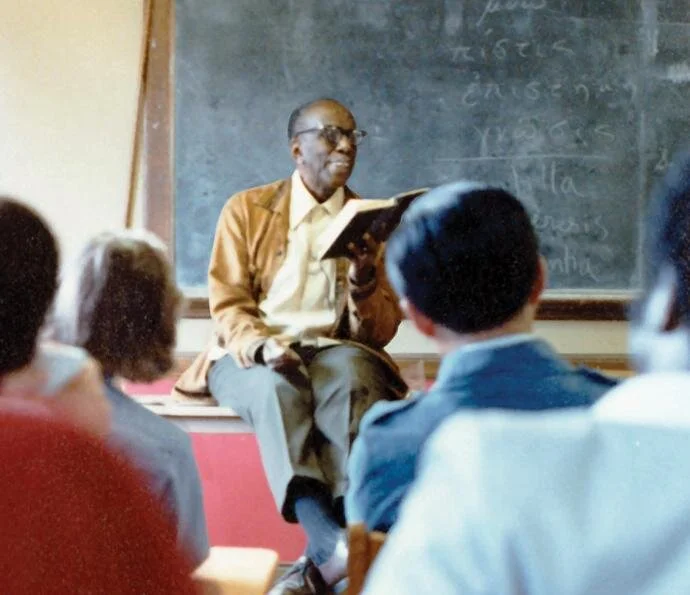

V. The wonderful thing is that we can comprehend the Rule of Benedict as a geography of everyday life not only for monks and nuns, but also for each of us. The Rule teaches that everything we do, especially those ordinary and sometimes dull and monotonous things, have the capacity to bring us closer to God. It is that useful and that relevant. A personal note here: in my years as a school person and academic, I have read and re-read the Rule as a means to become more ordered and compassionate in my daily work life and more centered, creative and consistent in my daily spiritual life. I have also used the Rule as a foundational document for leadership, community and service. I cannot imagine not having had this “rule” for guidance and wisdom.

VI. What drives both the text itself as well as our encounter with its content, are the three vows that the Rule articulates: Stability, Conversion of Manners, and Obedience with a very specific focus on Humility. In the spirit of an “interactive” Friday Reflection, and possibly by way of offering a very useful exercise, may I suggest that, in this time of COVID-19, we examine how we might understand these vows and how they might shape our everyday lives. How amazing that this man, Benedict, now more than 1500 years ago, could offer us some clues about how we might live, especially in this time of fear, anxiety, and uncertainty.

Loving Father…give us grace, following the teaching and example of your servant Benedict, to walk with loving and willing hearts in the school of the Lord’s service. And let your ears be open to our prayers, and prosper with your blessing the work of our hands…

—Appointed Collect for the feast of Saint Benedict of Nursia

Amen

—Father Peter Kountz