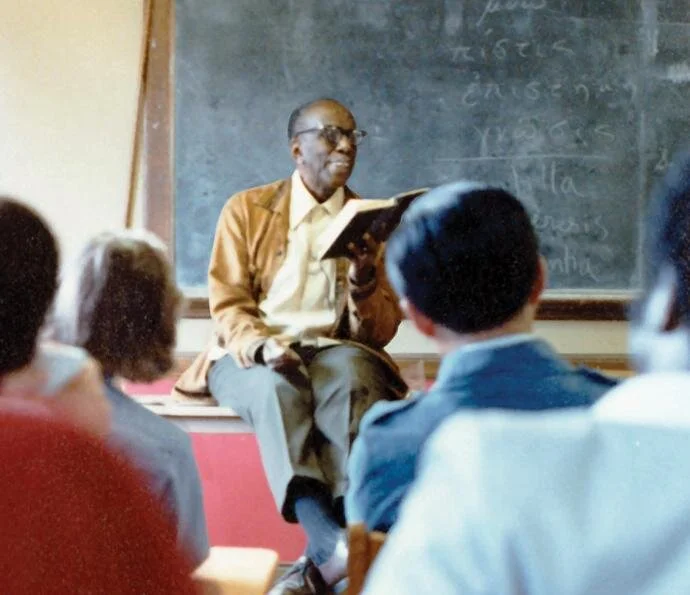

Friday Reflection Part I: On James Weldon Johnson, 1871-1938

Read the biography of James Weldon Johnson from A Great Cloud of Witnesses. The Episcopal Church commemorates James Weldon Johnson on June 25.

I will not allow one prejudiced person or one million or one hundred million to blight my life.

I will not let prejudice or any of its attendant humiliations and injustices bear me down to spiritual defeat.

My inner life is mine, and I shall defend and maintain its integrity against all the powers of hell.

— James Weldon Johnson

I. When I was growing up, my mother, a concert pianist, was often gone for performances in other cities, mostly in the Midwest and Northeast. My father, a music critic, was frequently gone in the evenings to review concerts, sometimes in other important area cities. Also, my mother was a college professor and my father a plant manager, so days and night were often complicated. My brother and I attended school just three blocks away from our house, so no one had to drive us there. To their credit, my parents saw the complications of their work and travels and their often irregular schedules and thought a great deal about how my brother and I could be cared for, watched, and loved. They decided to look for an “au pair” and found an older woman who, as I’ve thought about her, was just right for our family. She lived with us and was loving, ever-attentive, fun and funny, worldly wise, deeply religious and spiritual, and full of wonderful stories. I know that this unusual woman had a lot to do with my growing up, as she was with us for the first 12 years of my life. The remarkable thing is that it was never a matter of her being “in place of” my parents, especially my mother, but rather her being “in addition to” my parents. When I was 12, my older brother, who was 15, died and had it not been for our au pair, I don’t think I could have managed, for while I was taking care of my parents, she was taking care of me. She helped settle me after my brother’s death and then decided her work was done and it was time to retire so she could return to her family. Elnora Hayes was African American, and it was she who gave me the lens through which I could see a person exactly as he/she was and accept that person completely; that there were no conditions, no impediments to full acceptance. This lens, clear and unmarred, is one of the greatest gifts of my childhood.

II. Ralph Ellison’s novel, Invisible Man, (1948) has been a very important book in my life. I’ve read it several times and often taught the book in my high school and college classes. Its importance is signaled in the first paragraph of the Prologue: “I am an invisible man—I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids—and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you sometimes see in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me, they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination—indeed, everything and anything except me.” I have continued to read Invisible Man because it is so contrary to what I learned through the lens that Elnora Hayes gave me in the formative years of my life. Ellison’s reality is racism, something powerful, repugnant and ugly, a reality that Ellison demands that we see. This is not the reality in which I grew up and, for years, not a reality that I fully acknowledged.

III. I am writing this reflection on the very day the Episcopal Church remembers and celebrates James Weldon Johnson, whose story is all about achieving greatness in spite of his “invisibility.” It is revealing that in his novel, Ralph Ellison does not give the “invisible man” a name. He is only the “I” of the narrator. And this person, is meant to be our “eye,” the lens through which we see and don’t see; the lens through which we “see” invisibility. This “lens of invisibility” can offer us a very useful perspective on James Weldon Johnson and his exceptional gifts and his stunning achievements.

IV. Look again at the quote from James Weldon Johnson with which I began this reflection. It describes the reality in which Johnson lived, the reality of Ellison’s “invisibility,” what Johnson refers to as “the powers of hell.” Now, consider the arc of James Weldon Johnson’s life. Johnson was a major cultural figure in the United States during the first half of the 20th century and a person who was a school teacher and principal, a lawyer, a diplomat, a well-regarded and widely published poet, a novelist and essayist, a journalist, an educator and academician, a political activist and social justice advocate, a successful Broadway song writer and producer, and the Executive Secretary of the NAACP. James Weldon Johnson was also one of the founders of the Harlem Renaissance, the important African American cultural movement that created new art, literature and literary criticism, poetry, music and social commentary. Imagine accomplishing all this in 40 years of one’s professional life while always wearing the cloak of invisibility.

V. We think we know ourselves and our past but learning about the life of James Weldon Johnson can make us unsure about how much we actually do know, and most importantly, and perhaps as it should be, make us unsure of ourselves. James Weldon Johnson’s commemoration by the Episcopal church and the story that comes with it is meant to be a celebration of both the gifts and achievements of a supremely talented man. Can we see the greatness of James Weldon Johnson for what it is, without succumbing to the “cosmic powers of this present darkness” (from Ephesians 6:12, one of the appointed readings for today’s liturgy) and our fears of what is “different,” something we try so hard not to see?

VI. When I was in college in the spring of 1966, I took part in a civil rights march in Louisville, Kentucky, led by A.D. King, the younger brother of Martin Luther King Jr. It was my first protest march and I didn’t know what to expect. What came raining down on the marchers were ball bearings thrown by white men who had parked their cars on top of the hill that overlooked the road on which we were marching. While much of my experience is, now more than a half-century later, mostly a blur, I remember seeing the expensive cars of the “white men on the hill.” Imagine this perfect image of an America we know very well. This experience was a great lesson for me: I saw, first-hand, the clash of differences, of race, of privilege and exclusion, of poor and rich, of the Godly and evil, of justice and injustice. And even in 1966, I had no idea who James Weldon Johnson was nor that he wrote the verses to the hymn I knew, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” (1900) which was later adopted by the NAACP and dubbed “The Negro National Anthem.” Had I known better, and known what I know now, I would have gone to that hymn—and Weldon Johnson’s poetic verses—for solace. And this is what I would have found in the third verse:

“God of our weary years, God of our silent tears, Thou who hast brought us thus far on the way; Thou who hast by Thy might led us into the light. Keep us forever in the path, we pray. Lest our feet stray from the places, our God, where we met Thee, Lest, our hearts drunk with the wine of the world, we forget Thee; Shadowed beneath Thy hand, May we forever stand. True to our God, True to our native land.”

VII. It took me a long time, over a long and sometimes crooked journey with bumpy terrain, to realize that I needed two lenses, the lens of Elnora Hays and the lens of Ralph Ellison, to see real reality, and to discover and be discovered by the God of James Weldon Johnson. It took many decades, in fact. The violence, rage and murders of the last weeks have helped me understand these two lenses. In whatever way I can, I do want to stand in truth and justice with James Weldon Johnson and our common God, and to fight for the dignity and value of all human beings. I hope it is the same for you. Black Lives DO Matter.

Amen

—Father Peter