St. Teresa de Avila, Part II: Engaging with the Divine, the Devil, and the Carmelites

Monastery of the Incarnation, Ávila

Last week we left Teresa, after vacillating, consulting, and defying her father’s opposition, as she professed her vows in 1537 as a Carmelite nun.

We now ponder the monastery that she joined, which was very different from the original and its counterparts elsewhere.

The Carmelite nuns were a contemplative mendicant order added in 1452 to the older house of Carmelite friars (The Order of the Brothers of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Carmel), an eremitical [hermit] community established during the 12th-century crusades on Mt. Carmel in the Holy Land, a sacred site thought to be Elijah’s primitive refuge in the wilderness.

The order spread quickly throughout Europe with returning Crusaders. The friars’ original 12th-century Rule was mitigated (modified) twice to meet European mores and competition from other orders. The first, the mitigated Rule of 1247, absolved friars of living in the desert (especially after they were expelled from the Holy Land in 1291!) or total abstention from meat.

But they remained committed to a life of poverty and sharing what they had, residence in individual cells, a contemplative dimension in open dialogue with God, a life of charity, constant meditation on the Word of God, several daily communal prayer sessions, daily Eucharist, silence between compline and prime, communal meals, and manual work. The latest mitigation (1432) loosened the Rule to more closely resemble those of other mendicant orders.

The Carmelites’ charism (spiritual focus) remained contemplation, which included prayer, community, and service. Theirs was a fully cloistered monastic community whose service focused on its own daily chores (gardening, domestic work).

Upon their founding, the Carmelite nuns adopted the mitigated Rule of 1432.

Yet compared with other Carmelite houses of Teresa's time, Ávila’s Monastery of the Incarnation was strikingly relaxed and engaged with the world. By 1535, it was a vast, prosperous, and popular complex just outside the city walls, with no noticeable monastic structure. No Rule or Constitution has yet been found for the Incarnation during those years. Teresa herself reported the nuns who lived there were not cloistered and were free to travel. The monastery also housed the nuns’ relatives and servants and allowed visitors. Nuns wore luxurious garments and jewels. The community’s worldliness may have eased any of Teresa’s ambivalence upon entering: She could have a measure of both monasticism and worldliness there.

We still know little about novitiate training at the Incarnation during these years, though we’re aware of what Teresa didn’t learn then. She only discovered much later that a Carmelite Rule or Constitution existed. The known professions of vows at the Incarnation were simply to the Carmelite Rule, whatever that was. She herself claimed she was not taught to pray or to be recollected; she was on her own with books.

Her reference to recollection, nonetheless, tells us about the Incarnation’s spiritual vision at this stage, on a point that was bitterly debated in 16th century Iberia: the relative role of human will in life. Recollection’s opposite is abandon, the view that God left no room for human intervention; humans were thus guilt-free because God was responsible for all. Supporters of recollection, like the Carmelites, instead advocated inner dialogue and collaboration between the divine and human through a discipline of reaching for the divine within.

Teresa told us that, when she was dissatisfied with what other books prescribed for prayer and recollection, she turned to her uncle’s gifted copy of Osuna’s Third Spiritual Alphabet. She responded enthusiastically to that exceptional text, the most widely read and influential treatise of that time (and approved by the Inquisition), because it offered a path and attitude like no other. Yet even then she adapted his methods selectively, as we’ll see next week.

Teresa’s Rocky Road to Spirituality

Reading about Teresa’s pursuit of spirituality can also be a rocky road for the unprepared. So take a deep breath if you proceed since, I found, it involves a fascinating realm of human experience.

Teresa committed deeply to spiritual growth after her novitiate. Admiring a nun who suffered appalling illness with grace, Teresa asked God for a comparable experience to help her develop spiritually. She soon fell to a serious sickness whose disastrous treatment nearly killed her. She took medical leave in 1538, including stays with her sister and uncle, which provided almost a year of off-site solitude.

She saw her efforts at self-development as continuously assaulted by devils, without help from advisors. She struggled to learn inward prayer and contemplation. She could not manage “discursive thought [the background noise when focusing inward]” and felt she lacked the imagination to visualize for contemplation.

Her life was stressful in various other ways too. Over 20 years, she took several leaves—some scholars claim the monastery arranged them to remove her disturbing presence—because of repeated bouts of illness. She considered these as signs of divine favor for the effort to serve Him. She also retreated to confront the ongoing tug of the worldly: She developed what she considered unseemly love for two men she met at the monastery, which profoundly distressed her.

Two events around 1554, however, brought about what is now called her Spiritual Conversion. One resulted from an encounter with what she described as a devotional image [imágen in my 2014 Dámaso Chicharro edition] borrowed for a feast-day celebrated at the monastery. In her words (Life, 9:1): “It represented the much-wounded Christ and was very devotional so that beholding it I was utterly distressed in seeing Him that way, for it well represented what He suffered for us. I felt so keenly aware of how poorly I thanked Him for those wounds that, it seems to me, my heart broke. Beseeching Him to strengthen me once and for all . . . I threw myself down before Him with the greatest outpouring of tears.”

That pivotal image has been identified with several known works throughout Iberia. The editors of the 2019 Institute of Carmelite Studies English edition used here, Kieran Kavanaugh and Otilio Rodríguez, who translate the key term as “statue,” claimed it is one still venerated at the Monastery of the Incarnation at Ávila.

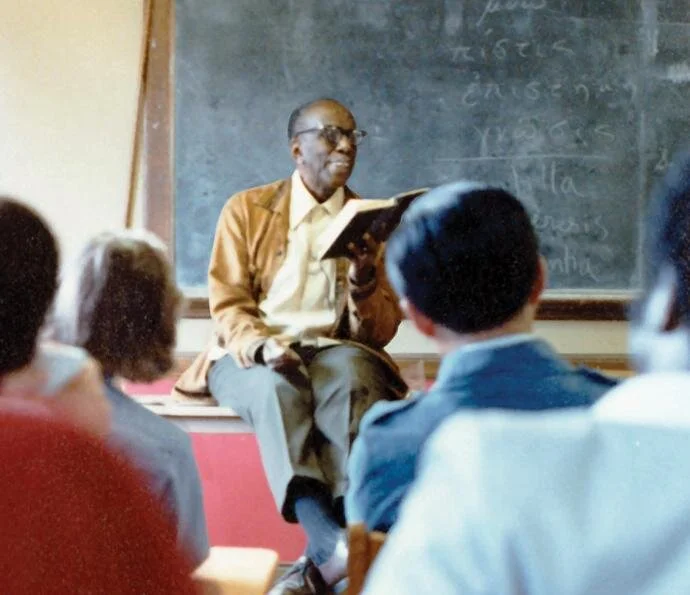

Juan de la Miseria, Portrait of Teresa de Jesús

In this encounter, however, Teresa discovered her own imagination and power to unite with the divine. She achieved contemplation through beholding an external form, an image. She could also respond emotionally to seeing Christ’s represented physical suffering. Her own body and emotions gained new authority in her spiritual experience.

Beyond testifying to his sacrifice, Christ’s represented wounds emphasized his humanity. Though some medieval writers dismissed acknowledging the human Christ as the lowest form of contemplation, Teresa fiercely embraced him as a flawed, suffering mortal like us. Even as others advised her to reject images, Teresa defended their inspirational and educational value, whether devotional or likenesses of humans (even her own portrait). Christ’s humanity also encouraged her to reinstate the corporeal as a vital complement to the spiritual in contemplation.

The other breakthrough that year came from reading Augustine of Hippo’s Confessions for the first time, by then available in Spanish (and permitted by the Inquisition). She was elated to find a towering religious figure who, like her, was a sinner who struggled with both spirituality and the worldly, lessening her fear that she was possessed by the devil or doomed to hell. Augustine also validated mystical ascent in stages, like hers, and gave her a language for spiritual experience that enriched the rest of her life as a mystic and writer/teacher.

Augustine’s work helped her, in the first place, to describe to Confessors and the Inquisition an escalated series of levitations and visions—mostly of Christ but sometimes of hell—over the next years that upset and embarrassed her if witnessed. Some of her advisors felt some were forms of demonic possession that required exorcism. She made “the fig [manu fica; an ancient gesture against evil]” at one vision of the Lord (Life, 29: 6).

She intensified “discipline” [fleshly mortification] to punish herself or to drive out devils until her confessors convinced her the visions came from God. She eventually lost fear of some and found solace and joy in others.

Her descriptions of such experiences to Church authorities are invaluable, among the most detailed in the mystical literature.

The piercing of Teresa’s heart

Take, for example, her compelling account of one episode of levitation or transport, for her a higher form of divine connection than union. God, she wrote, gathered up her soul, leaving behind the body that seemed to be cold and failing, yet delightfully helpless. Where in earlier cases she struggled futilely, this time resistance was impossible. She understood she was being taken somewhere mysterious. The divine transport “carried off the soul and usually, too, my head . . . and sometimes the whole body until it was raised from the ground” (Life, 20: 2-4).

Certain visions took place away from the monastery. The most famous came in 1560 at the home of her friend doña Giomar de Ulloa.

On one of several occasions when she was immobilized by the pain of love for God, she received a sublime response. She saw a rarity, a small angel in bodily form, close to her left side, with a flaming face and holding a golden dart that also flamed at the end. The angel plunged the flaming dart several times deep into her heart, leaving her even more paralyzed with joy and suffering. Her description of the sensation emphasizes its message of divine love. When the dart was withdrawn, she realized: “The pain is not bodily but spiritual, although the body doesn’t fail to share in some of it, and even a great deal. The loving EXCHANGE [my emphasis] that takes place between the soul and God is so sweet that I beg Him in His goodness to give a taste of this love to anyone who thinks I am lying” (Life, 29: 12-13).

Teresa has given us an unparalleled description of the interplay in mystical experience between the bodily and the spiritual, love and pain. This episode, however, doesn’t strike me as the consummate spiritual merging with the divine, as in levitation. Instead, it seems an extraordinarily loving dialogue between distinct entities, the divine and human. The mutuality of this expressed love reinforced Teresa’s vision of the relationship, as we’ll see.

For mystic ascetic St. Juan de la Cruz, her colleague and later founder of the Discalced Carmelite friars, Teresa achieved, with this experience, a height in mystical dialogue that few others had.

Accounts of this unusually violent divine encounter, once they spread throughout the Catholic world, set an ideal of expressed spiritual love, a model provided by a true event with a modern European. Particularly with this episode, Teresa de Ávila dramatically embodied the purifying, reassuring mission of the Counter-Reformation through its mystical dimension.

As she was beatified and canonized in the 17th century, images of her transverberation spread widely. Bernini’s Teresa in Ecstasy (illustrated last Friday) may be the most spectacular. But the many devotional paintings and prints like the one shown here were what the world at large saw.

Reliquary with Teresa’s pierced heart

Some later mystics reportedly received a similar transverberation. One is the Italian friar of the Minor Capuchin order who was later canonized for his mystical experiences and miracles, Padre Pio, whose side was pierced in 1918.

To return to Teresa, however, many scholars discuss the psycho-physical and orgasmic qualities of the episode. We might also consider it in relation to her actual heart displayed above the altar of the Church of the Annunciation at the Discalced Carmelite convent in nearby Alba de Tormes, now a pilgrimage site on the Camino Teresiano.

If it displays a mortal wound caused by supernatural piercing—far graver than stigmata in the hands and feet—in a nun who lived decades longer, this heart bears bodily witness to the mystery of mystical experience. Those who contemplate it, in turn, become human witnesses to the encounter, to its expression of mutual love, throughout time.

Following this extraordinary episode, Teresa’s interviews with Church authorities increased, giving her opportunities to testify to the phases of her spiritual path thus far. It also gave her a chance to explain why she wanted to found another Carmelite order. And it provided her an opportunity to articulate the stages of perfection through prayer that she had devised—and that continued to evolve afterwards.

Over her last years, Teresa would have many such sessions with Church authorities (and particularly Inquisitors), even in house arrest until high level Church and government powers (including King Phillip II) intervened. Everyone was skittish, responding to the slightest hint, provocation, and mood change. Teresa’s extraordinary mystical experiences and the vindictiveness of patrons who felt slighted by her community brought the authorities to her door.

As we can see, even cloistered monastics were vulnerable to Church censure in this period, though Teresa was never physically tortured or executed like other saints for their witness to the faith. As a late bloomer who struggled for long, like the illustrious Augustine of Hippo, she elicits our empathy. As a late bloomer, she also garners even more respect for her achievement in her last twenty years.

So stay tuned for the fruits of those years!

—Suzanne Glover Lindsay, St. Stephen’s historian and curator