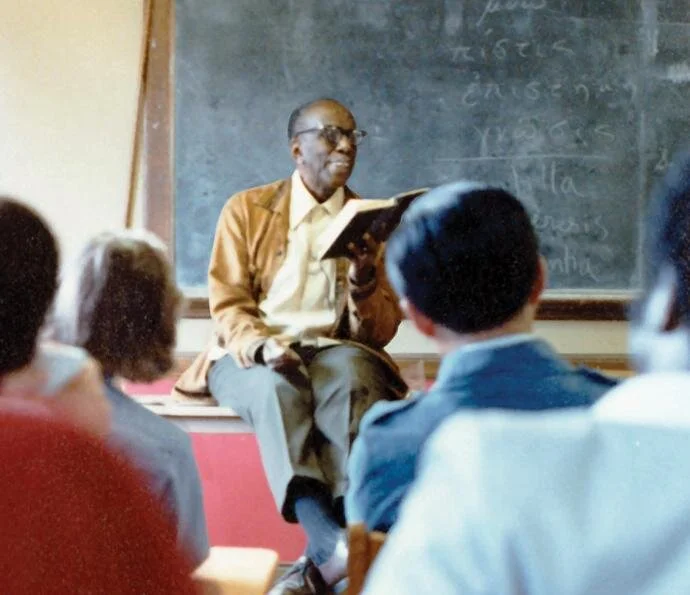

Personal journeys in spirituality, faith, and Church - Part 3: Mary Oliver (1935-2019)

Mary Oliver (1935-2019), award-winning, best-selling American poet, AND regular in St. Stephen’s virtual readings, offers a compelling model of an inner life without Church.

Mary Oliver. Photo: Molly Malone Cook

Oliver chose against Church after earnest study in Sunday school; she developed difficulties with the Resurrection among other points. Late in life when she revisited Christianity, she found she recast the Eucharist and Scripture according to her evolved alternative faith or spiritual vision (she used both terms).

For Oliver, spirituality grounded everything as “one of the most important interests of my life” especially since the beliefs that grew out of it affected lived or hoped-for life (Mary Oliver, “Listening to the World,” Krista Tippett, On Being [2015 interview, rebroadcast, updated, 2019).

Merging the spiritual with life in the world provided the underpinning of what I consider her religion, based on her view that religion helped “people feel that, alone, they are not sufficient, that they formed part of something larger” (Oliver, “Listening").

Oliver’s “something larger” was cosmic Community, with poetry as its sacred language. As a poet, she bore witness to the community of the world, created and inhabited by God, through the communal language of poetry, before the community of humankind, unifying them all.

This reflection, then, explores Oliver’s engagement with Community, which brought inner and lived lives, spiritual and physical worlds, into rich convergence through her poetry. That convergence as Community, then, includes us, her readers.

The world, the divine, and us

For Oliver, the physical world, inhabited by its divine creator, was the locus of Community as the “theater of the spiritual (“Long Life”). She consequently focused on this multi-dimensional world in an approach that attracted a wide spectrum of thinkers.

Her forms of engagement identified her, for professor of religion Debra Dean Murphy, as a “mystic of the natural world” and contemplative (“Why we need Mary Oliver’s poems,” christiancentury.org, 13 April 2017). Oliver approached the world mindfully by opening fully to her surroundings in humility and empathy, watching and especially listening convivially. She asked big moral questions of things large and small, yet dismissed reason, dogma, and answers in favor of mystery and maybe.

When approached in this way, the world, for Oliver, responded by dissolving its boundaries to engage reciprocally, to speak, and to address God’s presence within. She said little about seeking, much less seeing or hearing, God directly. Rather, she sought his manifestations in the multiplicity of his creations, their individuality and otherness, what she called “the multiform utterly obedient to a mystery” (“Long Life”).

Her poem “At the River Clarion” encapsulates her approach. She didn’t “know who God is exactly” or even if he existed. But if he did, he appeared in stunningly diverse “multiform,” from the sublime to grim and even catastrophic. God could be: “the tick that killed my wonderful dog Luke . . . forests, the ice caps, that are dying . . . the ghetto and the Museum of Fine Arts . . . the many desperate hands, cleaning and preparing their weapons . . . every one of us, potentially.”

She did not seek whys or solutions; she witnessed, felt, questioned, and found connection.

Elsewhere, she identified creatures that celebrated Community. This from “Wild Geese,” addressed to us:

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting –

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

These creatures spoke from within the “we” in their individual voices.

Language, communicated and heard, confirmed and enabled Community.

The language of Community, the poem, and the poet

As the language of Community, Oliver’s poems create community participation.

Through her first-person voice (the “I”) in her poems, she becomes us, our alter ego in experiences conjured by her words. The presenting and hearing/reading of the poem adds what she proposed, affirming ancient tradition, was poetry’s role as the sacred communal dialogue between the divine within the created world. Though her poems are mostly in conversational free verse, they, like most poems, declare their separateness from most prose especially in their sound when spoken/heard, and in their evocative call to the reader’s imagination and memory. For Oliver, the poem is complete only with the reader (Oliver, “Listening”). When the poem is read, the circle of cosmic Community comes to vivid life.

If poetry is a sacred communal language, then, did Oliver consider poetry prayer?

Oliver pondered prayer repeatedly in her poetry: its source (even animal or plant), what it is, does, and to whom. Her probing it as a distinct (if flexible) entity suggests that she considered poetic language a larger form that could include prayer. She also clearly entitled poems that are prayers (see below). Other poems are guides to prayer, like “Praying,” which closes thus: “[praying] isn’t a contest but the doorway into thanks, and a silence in which another voice may speak.”

Her own choice of prayer, given in “How I go to the woods,” entails private engagement with fellow creatures: talking to catbirds, hugging the old black oak tree, sitting so invisibly that foxes passed her without wariness. Her prayers could involve movement and speech but also stillness and silence. Attentive and present, all reached to connect. As published poems, they continue to touch well beyond, through time.

Her poem “Prayer” offers features of traditional prayer, however buoyantly irreverent. An expression of hope, even a petition, for the afterlife, it reaffirms her wish for continuing engagement with Community in new, revitalized form:

May I never not be frisky,

May I never not be risqué.

May my ashes, when you have them, friend,

and give them to the ocean,

leap in the froth of the waves,

still loving movement,

still ready, beyond all else,

to dance for the world.

With her death in 2019 at 83, we who complete this published poem by reading it continue to participate in it as poetry AND prayer, in Community across time.

—Suzanne Glover Lindsay, St. Stephen’s historian and curator