Part II: St. Stephen’s Farm at work

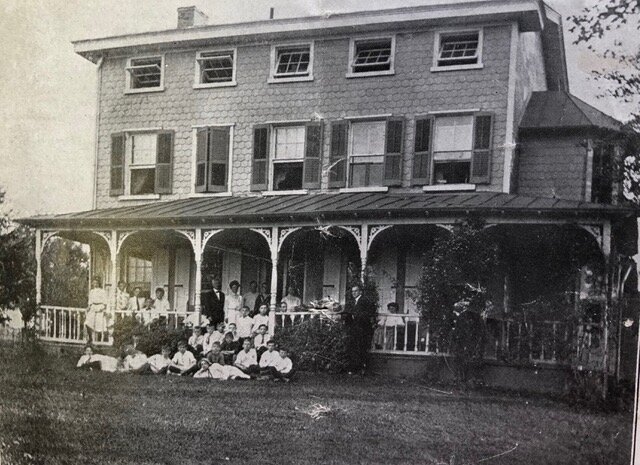

The winter sanitarium apparently disappeared quickly from the Farm’s activities. It’s possible it could only offer the older, simpler approach of rest and good food, rather than the new medical treatment for the recently discovered bacillus that proved the disease was contagious and treatable. The sanitarium’s disappearance from the Farm left summer as its only mission season. There is also no mention of learning skills or working while there; activities instead focused on restorative leisure. By 1902, however, Sister Elizabeth arranged for remarkably diverse guests from a wide range of Episcopal and city missions in Philadelphia. Some visited only for the day, given the Farm’s proximity by train. In addition to the poor in the Parish School, a party from the Home for Aged Couples came; the deaconess at the Church of the Crucifixion, a predominantly black parish, brought two parties of children; other groups from various Settlement Houses included black and Jewish children. The Jewish contingent is noteworthy since it may suggest that sheer hospitality could outweigh a traditional mission goal: To bring new members to the church through education and worship. Who, though, is shown at this outdoor service? Their summer attire seems remarkably fashionable even as Sunday best for the urban poor unless recently provided.

By 1905, however, St. Stephen’s sought contributions to recapitalize the Farm in extravagant language about its exceptional stature—and exceptional parish: “unique in church charitable work . . . nothing quite like it anywhere else . . . It is a living monument to the great-heartedness of St. Stephen’s congregation.” Was St. Stephen’s in fact unique? There is more to learn. It certainly inspired and supported later versions, however. The Church of the Crucifixion, previously guests at the Farm, bought its own for its needy parishioners for the same purpose in 1905—and came to St. Stephen’s for financial help to expand its space in 1906, when the program proved so successful.

St. Stephen’s own fund-raising campaign may have succeeded since the Farm remained active for at least another ten years. According to The Parish News of late 1915, the mission flourished. Reported attendance numbers were impressive: 396 [adults] for a week, 287 from the Parish; 109 from outside. 147 children came for one week (aged 10 weeks to 8 years). These were not child laborers, whose income was vital for their families; some stayed longer. The only quote from a child extolls the fact that she didn’t have to wash dishes for her large family for two whole weeks.

Some likely came with Sunday School groups recorded in the photograph shown above, once the program extended into the summer.

Yet new planned amenities seemed to turn away from the simple rural life. The administration aimed for a swimming pool, filled by the stream on the property, to replace Neshaminy Creek about a mile away; and possibly eventually an automobile rather than the horse-drawn wagon

Life at the Farm then dramatically changed, apparently without official explanation to St. Stephen’s congregation. After several years of merely cursory citation in The Parish News as a church mission and no mention in the vestry minutes, the Farm appears in the latter as it was being sold with no arguments as to why. In December 1919, the current rector, Dr. Carl E. Grammer negotiated its sale to Christ’s Home, a faith-based group from Philadelphia that moved to the country and built an orphanage there. By January 1920, St. Stephen’s tenant farmer’s lease was terminated. By April 5, there was a final agreement with Christ’s Home. There was apparently no mention of its sale in The Parish News. In 1923, Christ’s Home opened a residence for the aged at St. Stephen’s Farm that still exists.

What happened? The last presented budgets balanced; the farmer sold the Farm’s goods well. Changes in parish missions?

St. Stephen’s city activities seem to evolve in new directions in the late ‘teens, at times in response to current events that hit home, World War I, Spanish influenza. The church, it appears, recommitted to the city.

As it remains today.

—Suzanne Glover Lindsay, St. Stephen’s historian