Witness the birth of a cutting-edge instrumental titan: St. Stephen’s third pipe organ by the C. S. Haskell firm of Philadelphia

While St. Stephen’s celebrated Prof. Wood’s 40th anniversary as its organist in 1904, it dreamed of a new organ to suit the range and sensitivity he’d developed as a musician. The current Simmons arrived the same year he did, 1864, both luminaries of that moment. Prof. Wood, however, had grown since.

As in 1864, a major death within St. Stephen’s community soon opened a door. Eliza J. Magee, a lifelong congregant and patron of the church like her parents and siblings, died in April 1906 while the “hat” was being passed to fund a new organ. Her brothers and sisters immediately proposed to make the new organ a memorial to her by contributing $14,000, bringing the total funds to $15,000.

The elated vestry immediately authorized the Music Committee to negotiate for a new organ that cost up to that generous amount—more than three times the price of the $4000 Simmons in 1864.

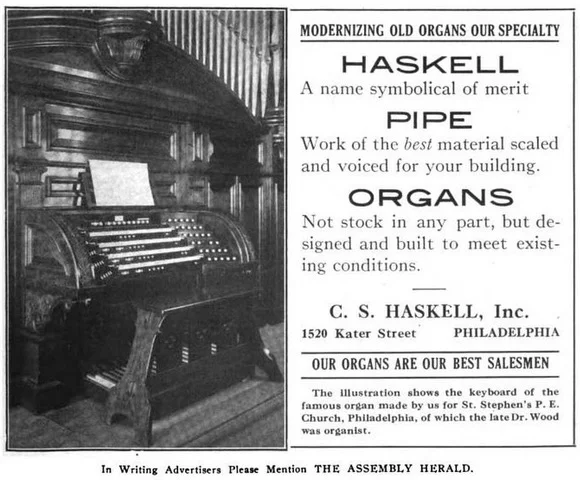

The Music Committee acted quickly and decisively. Within four months they announced to the vestry they had awarded the contract to “Haskell,” and that the organ was now being constructed.

The firm of C.S. Haskell, established in Philadelphia around 1888, was the first Philadelphia organ builder St. Stephen’s had ever chosen, despite the long tradition of resources here. Haskell had an excellent reputation for design, craftsmanship, and attention to voice. The firm built organs throughout Pennsylvania, New York, Delaware, and New Jersey. By 1906 Charles S. himself had died (1903); his son Charles E. had taken over the firm with William Fleming. They built St. Stephen’s organ to a scheme devised by its primary player, St. Stephen’s Prof. David D. Wood.

Presented as the Eliza J. Magee memorial, the organ was dedicated with a Consecration Recital in February 1907, with Prof. Wood at the keyboard.

This organ was a landmark for St. Stephen’s in several ways, including its ultra-modern technology: an innovative form of electro-pneumatic action. That means, instead of the recent short-lived battery-powered action (already beyond the traditional tubular-pneumatic action), this Haskell used an electric current to control air pressure, operated by the keys at the console, “to open and close valves within the wind chests, allowing the pipes to speak [to make music].” Thank you for organ plainspeak, Wikipedia!

Electricity was still a new technology at the beginning of the twentieth century but the church had already embraced it, thanks possibly to the Magees. Though the vestry had debated electrifying the buildings since the early 1880s, the Magee siblings had pressed for its introduction in 1890 to illuminate the mosaic reredos they had just given in memory of their mother (the Last Supper of 1887-9). The entire church complex apparently converted to electricity gradually, focusing on lighting in 1903.

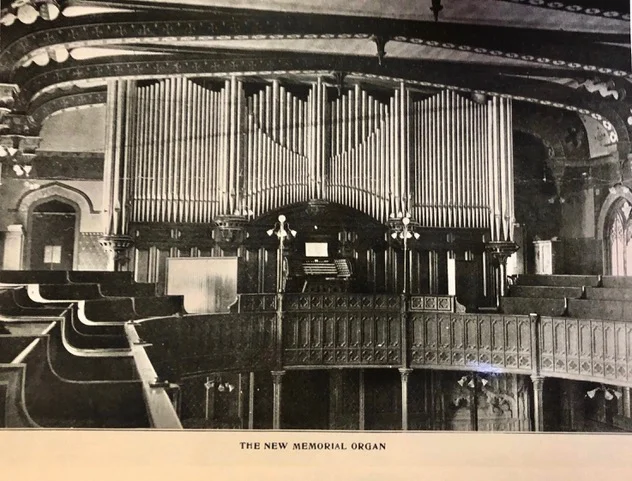

1907 view of Haskell organ

The new rector of St. Stephen’s, Dr. Carl E. Grammer, extolled the high-tech organ’s massive scale and materials: “one of the largest in the city,” he claimed. The main organ in the loft, he reported, weighed about 10 tons, in a black-walnut case that was 33 feet long and 18 feet deep, with 560 electro-magnets and cable, with 25 miles of wire. The combined length of the pipes, according to Dr. Grammer, was 4 miles.

Such technology permitted a new and powerful “surround sound” through a remote Echo Organ installed above the chancel, in the attic of the sanctuary 100 feet from the console.

St. Stephen’s Haskell was among the new “orchestral” pipe organs designed to accommodate a repertoire ranging from the Baroque, through the Romantic, to the contemporary. It produced myriad sounds from diaphanous to thunderous. To demonstrate, at the Consecration Recital, Prof. Wood played, among other selections, works by Bach, Mendelssohn, and Brahms as well as his own compositions.

The organ had four manuals and pedals, 64 stops, 66 registers, 70 ranks, and 4218 speaking pipes ranging in length from 16 feet to 2 feet. Contrary to the specifications recorded in the Consecration Recital pamphlet illustrated below, Dr. Grammer claimed the smallest was ½ inch—speak up, specialists, if that reported tiny pipe tells you anything, please. Its manual compass was 61 notes. Its pedal compass was 30 notes.

It delights me to see (in the illustrated specs) that Prof. Wood chose a Haskell Special 8-foot saxophone stop for St. Stephen’s Echo Organ. I wonder how he used it?

Leaflet for the Consecration of the Memorial Organ and Inaugural Recital at St. Stephen’s Church, Philadelphia (1907), courtesy of philadelphiastudies.org

The Haskell builders voiced the pipes within the church, producing, said Dr. Grammer, “a sweetness and just proportion of tone that reflect accurately the personality of the master who designed it and played it.”

This vast organ to the memory of Eliza J. Magee was simultaneously the creative partner and creation of David D. Wood—who played it for only three years before he died of pneumonia at 72 in 1910.

Forty-five years later, the Haskell was reluctantly dismantled after years of searching for options to keep it working, According to the organ builder who provided the present Wicks in1952, some of its pipes (but not, alas, the 8-foot Special saxophone in the Echo Organ) were incorporated into the new scheme.

But that’s another story. Stay tuned!

Thanks to Mike Krasulski, philadelphiastudies.org, for the photographs of the 1907 Consecration Recital brochure that came from our archives but apparently has disappeared. Your repository proves its value to us daily, Mike.

—Suzanne Glover Lindsay, St. Stephen’s historian and curator