When St. Stephen’s reopened with a new mission in 2017, the incoming team unearthed an unexpected feature of the church: Lying intact beneath the late-nineteenth-century annexes to the north was the original churchyard. Some tomb slabs became part of the floor but were repeatedly covered with carpet–and damaged in the process.

This discovery led the team, which planned simply to replace worn carpet and compromised flooring, to instead rethink the use of the zone—starting with the floor. That expansive surface, the team decided, would display all nine original vaults in a commemorative space to be called the Furness Burial Cloister, after the architect of the transept that covered them. The aim was to physically, symbolically, and ritually reintegrate the dead into the present, within a space with such varied history.

History of the church’s growth

A year after the church was consecrated in 1823, the vestry purchased and repurposed the narrow lot to the north as its churchyard, probably to plans by St. Stephen’s architect and congregant William Strickland. This intimate churchyard preserved a group of the congregation’s departed close by, as ongoing community even in death. It also gave the bustling city street a tranquil outdoor space for over fifty years.

The church eventually decided to expand the building to accommodate the congregation’s rapid growth.

In 1878 it commissioned architect Frank Furness to design a transept for additional pews and a new vestry room—to be built over the churchyard.

10 years laterArchitect George C. Mason Jr. replaced Furness’ vestry room with the present three-story Parish House.

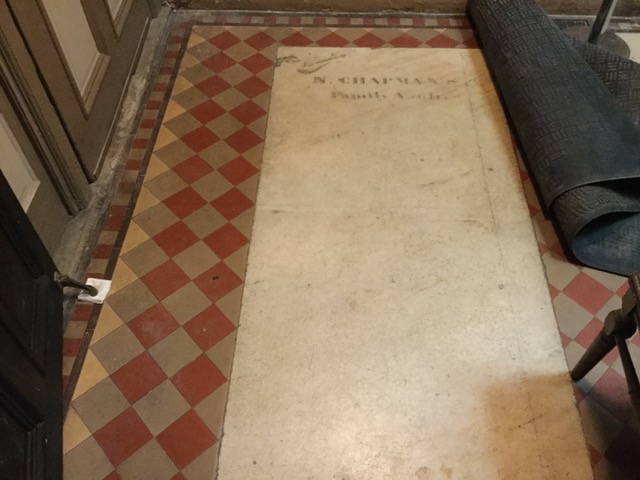

The precious open space was gone. And most of the vaults were lost to view and out of reach. Some were included indoors in new ways: Certain vault lids were exposed in the floors of the Parish House vestibule and transept, much like the slab-studded floors of Christ Church, where congregants had been buried from the beginning. Similarly, lids of the four taller vaults under St. Stephen’s transept floor were partially exposed in the bare pew floors. Yet they disappeared under Furness’ carpet in the aisles--until the aisles were later tiled (1896).

Slabs extending into those tiled aisles were visible for almost a century. When the transept’s box pews were removed in 1989 to create a new social space, the entire floor was carpeted, obliterating all markers.

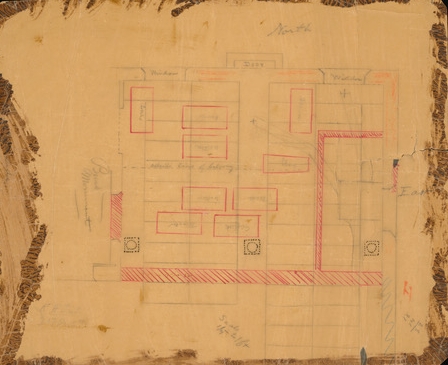

It even hoped to keep burying congregants there: The church archives contain a diagram of the transept that marks the vaults’ locations in and under the floor and pews.

Who is buried in the Furness Burial Cloister?

Find out whose vaults are featured in the Burial Cloister here:

The administration also publicly commemorated those thought to be buried in the transept and just beyond with a plaque with their names in the Parish House vestibule.

Yet the plaque bears glaring errors in information, and subsequent church guides only briefly mention the original cemetery as an early phase of church architecture.

Those buried at St. Stephen’s apparently lost their value to this changing congregation. So they disappeared from the collective memory even when in full view.

Why this ambitious remodeling project to honor the dead?

Prior generations may seem callously dismissive in their practical emphasis on the living in such compact urban space. Yet unlike so many publicized cases just in Philadelphia, St. Stephen’s tombs are still relatively safe, intact, and present (where remains were not moved by their family) in what is still consecrated ground—below (rather than beside) the congregants’ own church that now returns to life. So why bother?

This endeavor to honor the dead resurrects and updates St. Stephen’s earliest vision.

The church’s mandate in the 1820s, to include the dead among the living in its daily life, echoes within St. Stephen’s mission today, to embrace us all as fellow travellers in ways new and ancient.

Those interred in the transept, from 1825 to 1875, represent us all, individual lives, lived beliefs and experiences. Rich, modest, famous, average, or controversial, all came together as a community that shared the spiritual in worship and mundane activities. By inserting them physically among us, we honor the departed here as the human foundation of the church and neighborhood. Above all, we engage them directly, personally, as linked in Dorothy Day’s warmly egalitarian chain of being, across time and the mortal threshold.

In this dedicated space—so versatile in its historical, aesthetic, and metaphysical dimensions—we can meditate, ponder issues of existence large and small, gather to commune or perform, and even walk on the painted labyrinth that can be laid on the floor to symbolically enact the shared voyage of the living, departed, and those to come.

Construction and Design

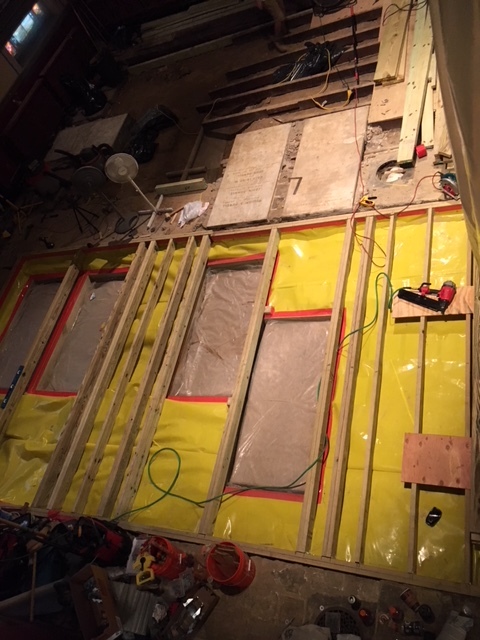

The project is coordinated and advised by historic preservation consultant Suzanna Barucco. The transept floor was removed to expose the vaults for examination and conservation. Restorers J. Christopher Frey and Vincent Iacampo then treated the marble slabs and reinforced their supports. Structural engineer Jonathan Price devised plans to support the replacement floor that will display the nine vaults. Four floor-level slabs will form part of the floor; the five vaults below the floor will be fully displayed under architectural glass, lit by an LED system designed by James Crowell.

Conceptually, the design presents an interpretive remodeling, rather than a restoration, to simultaneously evoke the multiple historical uses of the same space. Retaining the Furness annex but without the box pews that dominated it, the floor design will emphasize the vaults as a strong physical presence in a tribute to the original cemetery.

The floor’s design and materials evoke the various states of the original transept and link it with related areas in the conjoined buildings.

Two fields of wood floors will honor the transept’s box pews removed in 1989. Those wood fields will be framed by tile borders to evoke the aisles around and between the two banks of pews from 1896 to 1989. Rather than repeat the solid-colored stone and marble tile originally there, the new tile will be patterned to relate it to the tiled vestibule floor of the Parish House with its exposed slabs.

By calling attention to the buried dead in the onetime transept and Parish House vestibule, we honor those under the Parish House itself, unseen, most also still without names.

Furness Burial Cloister wins 2020 Preservation Alliance Award

We were honored to receive the Preservation Alliance Award for the Furness Burial Cloister project, completed in early 2019. Though it may seem purely about highlighting a noteworthy past, the project embodies who we are today, a community that breaks down barriers across time, change, and social difference to move forward.

The Furness Burial Cloister project itself, a remodeling of the church’s transept built over its original cemetery, has a fascinating history and many steps that were made possible by various terrific specialists. Check out the full story on this page