Friday Anniversary Thoughts—Connecting in Light 2: Nicodemus!

Atmore memorial window, Jesus and Nicodemus

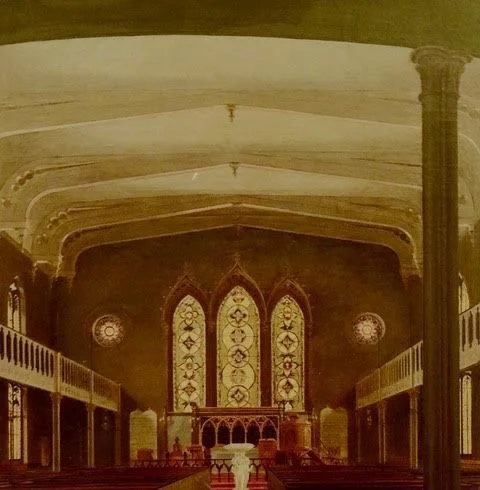

There’s a favorite today among the figural memorial windows given to St. Stephen’s in the early 20th century: the Tiffany window of 1911 presenting Jesus with Nicodemus on the south wall of the nave. It’s gorgeous, expressive and invites wide-ranging contemplation. Among other dimensions, it provides a compelling rendition of a familiar human dilemma given in scripture.

The window illuminates an encounter recorded in John 3 in which Jesus engages with the learned Pharisee Nicodemus, member of the ruling Jewish council (the Sanhedrin), who probes Jesus’ mission as the Son of God sent to save the world. Nicodemus acknowledges Jesus as a teacher sent by God but subjects him to a scholar’s exacting inquiry on details. John records only the unresolved exchange and its circumstances: at night since Nicodemus, despite his stature, fears retribution for approaching this unsettling new leader. Though some see scripture’s Nicodemus as adversarial, Tiffany’s image suggests a personal search. Nicodemus’ later objection to Jesus’ prosecution and presence at his burial (John 7, 19) signal, some say, his choice to follow Jesus.

Using the glass’ complex play with the church’s southern light, this window’s emphasis on represented light shapes the scene narratively (a night scene) and symbolically. It conveys Nicodemus’ search for enlightenment through his lamp whose rays connect both figures. The lantern also signals Jesus’ use of the word “light,” an ancient moral metaphor. Light, Jesus declared, is the sign of the truth he taught and embodied, as the Son of God, the opposite of dark evil. “[H]e that doeth truth,” he said, “cometh to the light, that his deeds may be made manifest, that they are wrought in God” (John 3:21, KJV). Tiffany’s lamplight at dusk and pivotal encounter at a building’s threshold reiterate Nicodemus’ spiritual crossroads.

The figures convey warm engagement in an intense situation. The prominent Pharisee leans imploringly, listening to the younger teacher who addresses him and signals openness with his right arm, and assurance and empathy by touching Nicodemus with the other. Their mutual gaze connects them even further.

The window’s concept becomes especially clear when compared with an acclaimed American version of a decade before by the Philadelphia black artist, Henry Ossawa Tanner.

Tanner, Jesus and Nicodemus, oil on canvas, 1899, PAFA

The two protagonists sit apart, radically differentiated in age but both Hebrew, unlike Tiffany’s classical types. There is no lamp: Light takes other eloquent forms. Contrasting with the cool moonlight washing over the nightscape, warm light radiates from Jesus’ chest along the roof terrace and steps as he gestures, tracing a path.

Compared to Tanner’s painting, Tiffany’s window renders comforting connection when searching or conflicted, amidst risk, crossing boundaries or thresholds to find one’s truth. Today, commentators frequently call someone in difficulty the new Nicodemus, like the active contemplative Thomas Merton who identified with Nicodemus in his search for his own “deep secrecy,” his hidden self beyond what others or his own ego admired.

How does this concept of Nicodemus apply to the man honored in the window? Robert E. Atmore (1842-1909) was widely respected as a successful Philadelphia businessman/manufacturer who devoted much of his life to the needy, notably the Spring Garden Soup Kitchen and the Church of the Crucifixion, an Episcopal church founded in 1847 by whites for poor black Philadelphians. He served on the church vestry until his last years. He also regularly (and apparently anonymously, as with most of his contributions) provided funds for their growing social programs and buildings, led by the church’s formidable black reformist rector, The Rev. Henry L. Phillips (1847-1947). Fr Phillips assisted St. Stephen’s rector Dr. Carl Grammer at Atmore’s funeral at St. Stephen’s in 1909. Three very different individuals collaborated across fraught racial and socio-economic boundaries for the same underserved, their work foundational for subsequent campaigns.

Nicodemus’ lamp in Atmore’s memorial window highlights his epitaph, which seems strange for such a private individual. The light may signal, as Jesus noted above, divine blessing of the man who served across borders with the truth that he found.

The Tiffany Atmore window honors the courage to confront difficulty; its emphasis on comforting engagement in turmoil lends welcome warmth to connection and continuity, along paths illuminated by light.

—Suzanne Glover Lindsay, St. Stephen’s historian and curator

About “Friday Anniversary Thoughts”

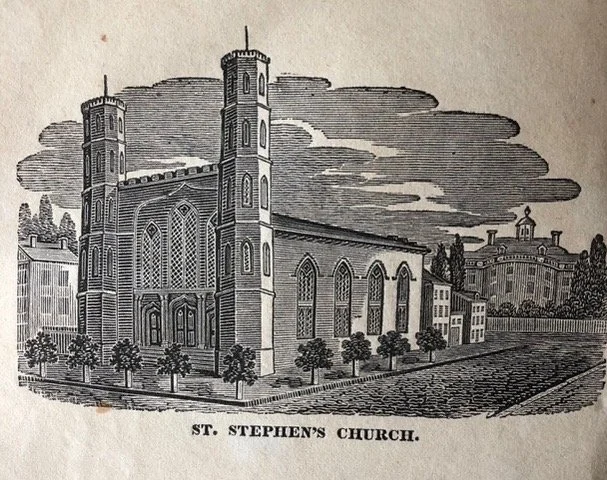

These Friday Anniversary Thoughts form part of a monthly series that began this fall to honor our 200th anniversary on February 27, and explores how our physical church embodies who we are and our mission since consecration in 1823. They turn to the message of key windows in the church today that were given over time. Find previous posts below.