Friday Reflection: Living with the Dead in 2020

Sign for Appalachian Burial Ground

I’m both serious and respectful when I claim that we live with the dead in 2020 perhaps more closely than ever. Though dominated by the elections, this week, which concludes a traditional remembrance of the faithful departed, made me realize how much the dead have been with us all year.

Most noticeably and painfully, I point to this year’s victims of Covid-19 and human violence, and the many whose deaths could not be mourned in person. But we’ve also had Ruth Bader Ginsburg pass from titanic mortal to titanic model and conscience in the afterlife for these troubled times. We’ve had political cartoons returning Thomas Jefferson to life to confront today’s judicial and constitutional debates.

There are many such dead who trigger strong emotions and reinforce our moral compass and intellectual standards for Now.

I feel the connection very strongly. It’s also an ethos of continuing bond and influence that I can trace as a specialist in 18th-19th-c French funerary cult, a field that studies what historians have long called, in all seriousness, “living with the dead.”

Considering the dead as still “US”

For various Western Christian communities and families, their identity and roots resided heavily in their buried dead. Separation was traumatic and neutralizing, whether for refugees from upheaval or residents of rural Appalachia whose homesteads were taken for dams or national or state parks.

Within that bond runs the abiding fear of the new power of the departed in death, to be acknowledged with attention on their specific anniversary days or a generic event, the harvest. For this last, we see a survival from older cultures that recognized the shift to winter as an opened portal for the living and the dead to directly interact (for instance, Samhain). Popular traces of that culture: The costumed “supernatural” visitors at Halloween demanding treats at your door, with possible reprisals if refused (a trick).

The Christian multiple-day of remembrance (31 October-2 November, in Anglo-Christian terms Allhallowtide, All Saints’ Day, and All Souls’ Day), eventually fused the latter two into one. The event historically featured a rite in which a parish priest led worshipper around a church cemetery to pray for the souls of the departed in Purgatory. For all our kinship as fellow mortals or blood family, those dead had become “other.”

Crisis brought about change.

Eighteenth-century France led the way in building a different relationship with the dead in the wide-ranging campaign for social progress especially in the cities. City churches and cemeteries grew overcrowded with reeking, decomposing bodies that, it was then thought, caused disease. The government closed city churches and cemeteries to burial and transferred remains to new common trenches outside city walls.

Given the importance of their burials, that move severed a link binding individuals, families, and communities.

The situation worsened in the 1790s as rapidly shifting Revolutionary governments struggled with priorities for social “regeneration.” While ordinary citizens and guillotined victims were dumped without rites into common trenches, the Revolution’s heroes (Voltaire, for example) received elaborate state rites and tombs.

Citizens complained bitterly that the Revolution’s funerary policies were anti-egalitarian and inhumane, including for those left behind, unable to mourn and honor their dead. One Paris lawyer asked, in a famous pamphlet, how could such a horror come from a supposedly advanced modern nation? France had dismissed society’s highest values. Any community’s burials, he claimed, were a measure of its morality. He echoed influential Enlightenment thinkers who asserted that burial was natural to man, a social creature. The government’s funerary policies showed the world that Revolutionary France perverted its own vaunted ideal, Nature.

Public criticism, framed in debates and activist literature, shaped new programs by 1804, when Napoleon became Emperor. The first was to prove France’s modern morality by revamping its funerary policies for cities.

To compensate for keeping churchyards and city buildings closed to burial, France established public neighborhood cemeteries with individual graves (paupers’ trenches survived, nonetheless), plots that could be consecrated, and designated sections for different faiths in some cemeteries. The largest and most famous today is Paris’ Cemetery of the East, nicknamed Père-Lachaise for its famous earlier owner, Louis XIV’s confessor.

These new cemeteries implemented earlier 18th-century proposals—especially in the poetry of the beloved Jacques De Lille—that presented the modern city cemetery as a modern Elysian field, a beautiful natural setting where the dead and living could peacefully mingle without the frightening or morbid warnings of the old church cemeteries.

The new cemeteries embodied the poets’ vision of the tomb as the “border between two worlds” where you came to honor and learn from national heroes, or to mourn and seek advice from your departed mother. Going beyond sheer memory, which responded to many cues, the physical presence of the departed within the tomb was defining, as with saints and martyrs. Rather than serving as channels to the divine, modern tombs were portals to actual people, lived experience and beliefs, across the mortal threshold. No longer were the dead “other;” they were a vital part of “us.”

France’s Jour des morts (the Day of the Dead) became a public event without organized activities, with families thronging into their neighborhood cemeteries to commune with the dead and their gathered kin and to clean and redecorate graves.

Today, the Jour des morts remains the prized occasion to see Parisians—not just tourists—converge on their neighborhood cemeteries, once again sites of rootedness and a living connection.

A New Concept Spreads and Evolves

Bench, Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia

Other countries customized France’s new cemetery model to their differing cultures and rites; most added outside landscaped public cemeteries to existing city churches and churchyards. Boston’s Mt. Auburn Cemetery (1831) and Philadelphia’s Laurel Hill Cemetery (1836) both responded to Père-Lachaise. Guidebooks use the language of France’s poets to instruct Americans in this new relationship with the dead, with the tomb in the modern Elysian fields as the consoling border between two worlds where the living and dead could commune. Writing of Mt. Auburn, naturalist Wilson Flagg claimed the friend’s voice emerging from his tomb in conversation deprived death of separation: “Does there not come up from [a friend’s] grave a voice . . . addressed to the heart and felt by the heart as the kindest and most serious tones of the living friend?” (Mount Auburn. . . . , 1861, 50). The familiar benches at the tomb or throughout the grounds accommodated such conversations or quiet mourning.

All Saints’ Day 2007, St. Roch Cemetery, New Orleans

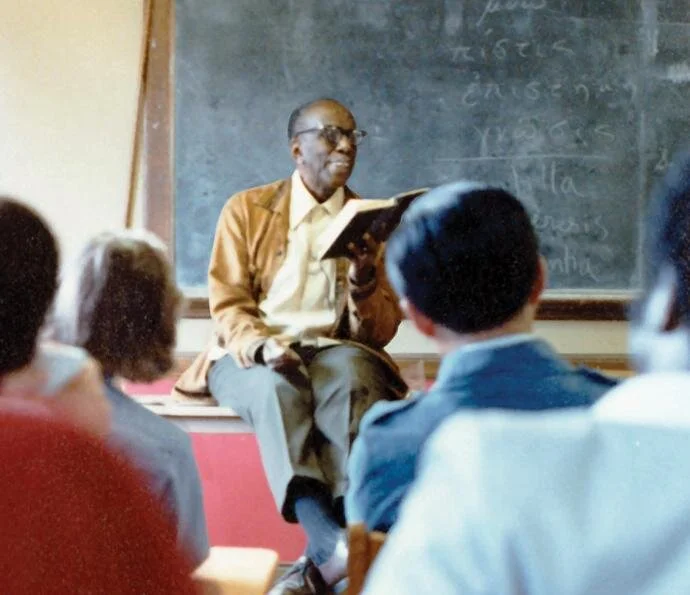

I’m finding few counterparts to Paris’ secular Jour des morts rites in our immediate vicinity today, though I’m just learning the varying deathways in the United States. At least one of New Orleans’ famed cemeteries, in this case a Roman Catholic one, offers cemetery masses for the dead on that day; the living bring chairs to also sit with the buried departed

Our own Memorial Day for fallen soldiers began in 1868 as a remembrance and cleanup day for the Confederate fallen, a rite in May known as Decoration Day. It spread to the Appalachian region as a general community event for its dead that continues to this day. Families gather from miles away on Decoration Day to clean up and commune with their dead and kin in cemeteries that were preserved within the parks (

Decoration Day, Appalachia

Again, a sense of community and roots. The modest wood sign first illustrated in this Reflection supposedly belongs to one such community, affirming values forcefully stated in crisis in remote 18th-century France.

The Plight of the Anglo-Episcopal Dead

The Anglican Community had a problem with its dead that stemmed from the Church’s struggle to reconcile traditional Christian beliefs and practices with newer Reformation modes. Adherents of the latter (often called Evangelicals) rejected older funerary practices as “popish” and corrupt.

The Anglican concept of the afterlife remained ill-defined, allowing various views that appear on tombs and in popular literature. Souls were often rendered as going straight to their eternal home (predictably heaven. . . ). If so, why pray for them, asked Evangelicals.

ES Burd Canopy tomb, 1849-53

In the early 19th c., the eminent Episcopal bishop of New York, the Right Rev. John Henry Hobart drew from Scripture a vision of a temporary Paradise for the faithful (and an alternate zone of temporary suffering for the sinful), as all awaited the Second Coming and Resurrection, that influenced later English Tractarian views on the subject. Evangelicals condemned the Tractarians’ proposal as popish Purgatory.

The Hobart-Tractarian vision may appear in Edward Shippen Burd’s funerary monument at St. Stephen’s, presenting his soul resting in an invisible Paradise among us but made compellingly present in the canopied marble.

We are ever aware of his patient wait in death as we move around the church in life.

Today, though Anglo-Episcopal beliefs and practices still vary (some Anglicans pray to saints), the Church offers prayers for the dead. For Fr. Greg Goebel of the Anglican Church North America (anglicancompass.com), we are praying for our peers as ever. Scripture, he wrote, assures us that the dead and living remain “One Body,” a community in Christ who holds us all together in “one communion of the saints . . . so we are with them and they with us” as we all await the Resurrection.

Furness Burial Cloister

St.. Stephen’s reaffirmed its commitment to its departed community when, as part of its remembrance rites in November 2018, it began its mission to integrate part of its original 1825 churchyard into the 1878 transept that covered it. We later found cinerary urns in the onetime transept’s west wall for a later rector’s sons (and possibly the rector’s). These older members of the community are now more intimately part of our daily life, of us as fellow travelers

With the resurgence of Covid-19 this fall, this long remembrance weekend found some cemeteries, open through the summer, to be closed.

Covid Memorial

Sitting in isolation far from home, I travel mentally to join departed loved ones and those who’ve died this year and their circles among us the living, all one community. And I’m grateful for remembrances in public spaces that I see on the internet. Virtually, I join a community gathered there, the living and the dead. I’m so glad for us all.

—Suzanne Glover Lindsay, St. Stephen’s historian and curator