Friday Reflection: The Power of Music: St. Cecilia

Guercino St. Cecilia

Father Peter was called away suddenly so I jump in, a week early, to consider St. Cecilia, honored on her execution day, November 22, also the day JFK was shot in 1963.

St. Cecilia counts among the most famous Christian saints. She’s one of the earliest Christian martyrs in Rome (martyrdom automatically qualified her for sainthood). She also came to personify music, sacred and secular, especially since “classical” music draws deeply on Western and Eastern liturgical music. But she also embodies musical inspiration, the creative imagination of the composer and performer.

The more I learned, however, the more intriguing, polemical, and thought-provoking her story became. It’s such an important story that there are reams written about her over the centuries. Here, I’m going to briefly touch on specific points for reflection.

Her primary and earliest biography is the Acts (or Passion) of St. Cecilia, written, it is thought, around the 5th c. C.E., but quickly spread throughout Europe and the Eastern Christian world as the foundation for most later images and texts.

Those resources, however, failed the more recent test of historical analysis even by the Roman Catholic church. There is no consensus and little historical proof of when she lived (2nd/4th c. CE?), her class, her family—even her personal name. Several preliminary burial sites have been proposed. St. Cecilia may even fuse two historical figures.

Her biography, scholars and Roman Catholic authorities have concluded, was gradually fabricated from factual wisps, even fantasies. Not unlike Merlin and Arthur. She took form shaped by the needs of the Roman Catholic church and community over time. In her case, we can see the church’s quest for exemplary converts to the new and beleaguered faith, for advocates and martyrs among “us” (Western Europeans), for sacred places and relics (physical witness and sites of divine grace) to encourage belief and growth.

Backed by the Roman Catholic church, Cecilia-as-musician became the powerful figurehead of the development of Latin (Western) Christian liturgical music after the Middle Ages, especially as such music faced growing condemnation by the Protestant Reformation. As it still does, as we’ll see.

Today, as we ponder the Church, worship, spirituality, and ourselves as Pandemic shapes the path forward, the role of music is very much alive. How can it fit today in our evolving view of the sacred, of spirituality, social bonds, and experience, personal and collective?

Cecilia: Martyred Musician

I’m going to bypass the vast historical analyses of her story to focus exclusively on Cecilia’s emergence as a musician in the foundational text, 5th c. Acts that went “viral.” It’s a chatty, openly partisan Christian biography initially in Latin, about a privileged Roman woman, a secretly devout Christian whose “idolater” parents promised her in marriage to another wealthy Roman “idolater,” Valerian. Cecilia consented, aiming to persuade Valerian to meet her terms, chastity in their union (given her mystic marriage to Christ), which she did. She also aimed to convert him to Christianity, which she also did, among many others before they were both martyred.

The key event that associates Cecilia with music appears at their wedding. As the musicians played, Cecilia reaffirmed her fidelity to her celestial husband Christ by singing “in her heart only to God [cantantibus organis illa in corde suo soi domino decantabat].”

Over the centuries as her cult grew with Christianity, the Latin passage was apparently recruited to associate Cecilia with music. One telling sign: Her imagery shifts from the evangelizing bride (notably Valerian’s baptism, seen in a 9th c. image) to her musical guise as early as the 14th century. More specifically, she became identified as an instrumentalist, an organist, a change that occurred as the organ gradually gained acceptance in Western European liturgical music. The instrument was played during services in churches in Rome and England in the 7th to 8th centuries; many consider the process of assimilation complete in the 15th century. St. Cecilia’s career as patron and personification of music was launched.

The organ’s acceptance in Roman Catholic congregational worship signaled the widening of the role and character of liturgical music (including more instruments) throughout Europe and the Americas, though not in eastern Orthodox churches. It also opened more professional avenues for composers and musicians in all regions.

Cecilia’s symbolic prominence in the process appears in the founding of national academies in her name throughout Western Europe. One of the oldest, the National Academy of St. Cecilia in Rome, was founded in 1585, with St. Gregory as Cecilia’s co-patron, subtly marking his realm (plainsong or a capella choral music) and hers (music with instruments). The Cecilian Academies eventually became prestigious centers for music and the arts of many kinds, drawing artists from all over the world.

The problem with instrumental church music

The surge in instrumental church music in the 16th century, presided over by the musical Cecilia, escalated the war with the Reformation underway primarily in northern Europe. In their mission to return the Church to its essences, to true worship of God and His word for everyone, many reformers condemned medieval monastic music like the Gregorian chant as unsuited to congregational worship. They objected to its use of Latin, a language alien to the lay worshipper who thus could not participate.

With the addition of dramatic choral music (cantatas, oratorios), increasingly elaborate instrumentation and vast organs, reformers accused Catholics of wasteful extravagance, overweening vanity, theatricality, and sensuality—sins stemming from the unbridled power of music.

Such music deviated from reformers’ view of music’s true role within worship, as conveying words from Scripture in languages that the congregation could understand and sing: hymns.

Though all reformers condemned Roman Catholic musical “excesses,” they acknowledged that the French John Calvin (1509-1564) was the most severe and comprehensive among them. His elder in Germany, Martin Luther (1483-1546), himself a fine instrumentalist, vocalist, and composer of hymns, instead proposed a middle course to support church music, vocal and instrumental. For him music was a divine gift. Music was next to theology in importance for its power to inspire and convey devotion to God, to elicit emotion and aesthetic pleasure even without Scriptural words, avoiding the sinfulness that he associated only with bawdy secular songs and dancing. With his influential support, great Lutheran hymns, chorales, and great instrumental music were composed, performed, and published, many by Lutheran luminaries like Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750).

Today’s organizations of Lutheran church musicians, significantly, are dedicated to St. Cecilia.

Yet today, the musical St. Cecilia is still embroiled in the struggle over instrumental liturgical music, as we can see in a reading of Raphael’s famous rendering of her wedding.

Raphael St. Cecilia, 1513/17

Raphael adds Cecilia’s ecstatic vision of the angels responding to the silent song described in the Acts. Where one author of 1968 claims Cecilia called the celestial beings with the portable organ in her hand, another sees her repudiating all earthly instruments in favor of the celestial sung hymn of praise.

Any internet search today confirms the ongoing hostility to instrumental music in certain churches: some Eastern Orthodox churches, with their abiding tradition of chant, and Western churches such as the Church of Christ and the Seventh-Day Adventists, who follow the primitive church that avoided the instrumental sacred music of the Jews recorded in Scripture.

Where does St. Stephen’s fit?

Within the musical spectrum of the Anglican Community, St. Stephen’s tends towards Luther since the congregation sang hymns accompanied by an organ and professional choir, who also performed chorales, with the organist playing solos in designated places in the liturgy.

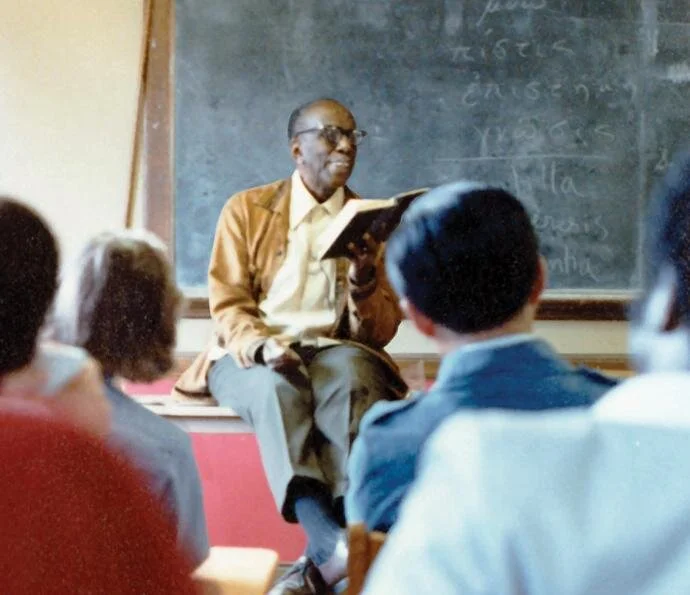

Instead of St. Cecilia presiding as the personification of our historical commitment to music, we have, prominently displayed in the nave, a large marble memorial to our own beloved and nationally known organist-choir-master-composer from 1864 to his death in 1910, David D. Wood.

David D. Wood

For all his high reputation and long memory, he stands for the various musicians-composers at St. Stephen’s since its beginnings in 1823. Among them (listed for the first time) are William Henry Darley (St. Stephen’s first), Charles Boyer, William H. Fenney, H.G. Thunder, Edward Shippen Barnes, and H. Alexander Matthews.

Music and Pandemic

Finally, we consider Cecilia the creative spirit of music, which she embodies dramatically in her spontaneous song (silent or otherwise) in the middle of a raucous wedding.

For us, she might well celebrate today’s huge creative energy stemming from . . . Pandemic. Even as some communities cautiously regroup in familiar modes adjusted for Pandemic (we’re all haunted by the church choir that contracted Covid19 in rehearsal), our global community, our stage in lockdown, has become the internet; our medium, electronic. I’m glued to YouTubes of Alvin Ailey’s troupe dancing a familiar piece, each dancer in isolation, assembled electronically; of chamber groups and baritone soloists performing in various roles, reassembled electronically. Paid virtual concerts (finally, money!). Familiar artists recast their stage presence and sound here; new artists enter the electronic stage. Many—composers, performers, audiences—create, hear, and visualize in new ways. Old forms are revisited, with new meanings, contexts, and audiences in this world in flux: Fr. Peter reminded me of the renewed interest, in the pandemic world, in John Cage’s innovative explorations of sound and silence, like 4’33 (available, of course on YouTube).

What about religious and sacred/liturgical music? I tentatively equate the latter two, per Bishop Thomas Olmsted’s definition of both as sacramental, performed as part of the liturgy, vs. religious music as the earthly expression of a given culture’s faith. As we rethink the church, liturgy—the whole package—Pandemic encourages another Reformation, another search for the essences of the church. Liturgical music? If, as Bishop Olmsted (who is Roman Catholic) says, the mass is essentially a song, then we have a lot to work with.

Pandemic has unbound me beyond the wide range I’ve cherished since childhood: early monastic music, that of the Sephardic diaspora, the classics from Victoria to Britten, Ariel Ramírez’s Misa Criolla. I now crave more scope, less rigid definition and exclusions, more in-between spaces, as long as I hear respect, humanity, transcendence, and a spirit and imagination that carry mine with them: that’s the religious definition of rapture, ecstasy. For that experience I turn to Hildegard von Bingen’s mystic pieces, evocative sound-vehicles of visions like Cecilia’s. Or Fred Hersch’s meditative jazz piano solos and ensemble piece, Leaves of Grass. Calvin might rail at me but Luther would reiterate that music is a divine gift whose emotional transport is a form of pure devotion.

Among the many pieces composed during and for Covid19 lockdown, one, shared on Facebook, especially touches me. Entitled “Quarantine Song,” it’s a Vocalise (a vocal work without words) performed by a much-noted young Polish counter-tenor Jakub Jósef Orliński (also a breathtaking break-dancer) and his frequent accompanist, pianist Aleksander Dębicz. I saw/listened to it on my iPhone, sitting on a park bench, and later at home, on my 22-inch computer screen. Performed in an intimate apartment, “Quarantine Song” is, for me, powerful music that mysteriously reaches important places without words. Each of us perhaps hears our own song within it and, I hope, finds transcendence.

—Suzanne Glover Lindsay, St. Stephen’s historian and curator